First primate born from frozen testicular tissue offers researchers hope to preserve the fertility in young boys undergoing cancer treatment.

This baby monkey Grady is the result of a new study done at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, USA, and she marks a big step forward towards the possibility of preserving the fertility of young boys.

Cancer treatment with medications such as chemotherapy or radiation increase the risk of infertility. In men, the treatment can damage the production of sperm, and therefore, men in fertile age can have their sperm frozen before cancer treatment. Young boys however, do not produce sperm until puberty and today there is no technique that can help them have biological children in the future.

In this study, researchers removed and froze testicular tissue from five juvenile rhesus macaques that were too young to produce sperm. One of the monkeys was Grady’s father. The monkeys were sterilized and when reaching puberty, the tissue was thawed and grafted back into the monkeys. One year later, the testicular grafts were removed and examined. The previously immature testicular tissue was now producing testosterone in amounts high enough for the monkey to undergo puberty and they contained mature sperm.

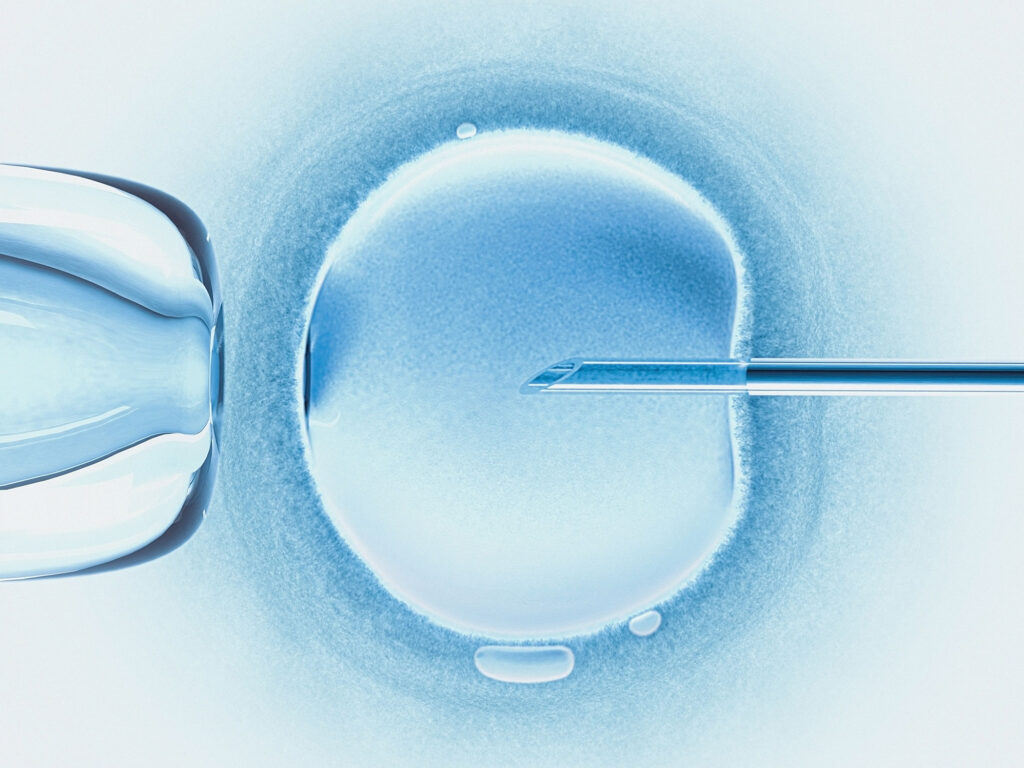

The mature sperm was extracted and used to fertilize eggs by intracytoplasmic sperm injection. The procedure resulted in 138 fertilized eggs and 11 of the resulting embryos were transferred into female macaques, which resulted in one pregnancy and subsequent live birth – little Grady. The findings have been detailed in the journal Science.

Claus Yding Andersen, professor at Rigshospitalet in Denmark and part of the ReproUnion project, is discussing this important finding and how Grady can pave the way for young boy’s possibility of having biological children after cancer treatment in the radio program “Så vidt vi ved” on Danish P1. You can read about the news and listen to the program here (only in Danish).

Already today, testicular tissue from young boys are stored at Rigshospitalet in hope for the technique to advance and it is likely that in 20 years, where these boys will be old enough to be wanting children, the technique will be available in humans.